“The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.” ~Joseph Campbell

My husband Jake and I sit in anguish on our beautiful new linen couch, inches away from each other, yet worlds apart. Hours of arguing have left us at another impasse, the stalemate now a decade long.

I look around in despair at the beautiful life we built together, petrified by the decision I know I have to make. My partner, my friends, the country I live in, the ground beneath my feet—all on the brink of collapse.

I stare at the ceiling in heartache. What will be left of my life? So begins my descent into the white-hot heartache of letting things die.

Lost in Translation: Identity and Adaptation

I’d moved from Australia to the United States ten years earlier to be with my soon-to-be husband.

This wasn’t a particularly dramatic move for me. I’d spent my whole adult life up until that point traveling and living in foreign countries and, although there was always a natural adaptation period, I managed. In fact, I loved it—I feel born to be foreign.

So I thought this would be similar; straightforward, even. But I was wrong.

The nature of being foreign is unfamiliarity. Each day feels like a fragile dance between two worlds that requires a huge amount of personal strength, emotional generosity, and energetic adaptation, because you are perpetually read from a different worldview, which means you likely feel constantly misread and misunderstood, even when you speak the same language.

Along with that, and the other difficulties inherent in making a life in a foreign culture that I had learned to deal with—having no outlet for huge parts of who I am, constantly navigating an environment that reflected nothing of my values—I now also had to reckon with the need to adapt to my partner’s lifestyle. I needed to be friends with his friends, take the vacations he wanted to take, and fit myself into the predetermined role of “wife” in his life.

We made large-scale decisions that seemed like compromises at the time, and I was often genuinely happy to make them in the name of the unit. But with each compromise, a piece of my identity slipped away, and I eventually realized how much of what was true to me was being weeded out of “us” and how little importance I was placing on my own desires and happiness.

I became deeply alienated in my life and my marriage. I stretched myself so far outside my own skin that maladaptations started to occur. I would find myself in conversation with friends saying things that felt like they were coming out of someone else’s mouth.

In trying to survive, I’d created a life that reflected little to nothing of my truth, a life that was emotionally, psychologically, and spiritually starving me to death.

But even when I realized this, I couldn’t bring myself to end it. Deconstructing my half-life seemed worse than living it. I knew it would spark a tsunami of such unknown proportions that it was an absurd decision to make. So I didn’t.

For months, I coped with my unhappiness, convinced it was better than starting all over with nothing.

Confronting the Inevitable: Embracing Endings and Loss

A few years ago, I joined a group that met monthly to grow in death awareness and reckon with the grief and heartache of the little and big endings that occur in each moment, month, year, and lifetime, in preparation for our final ending—death.

Through it, I realized that I was avoiding the death of my relationship, for fear of enduring the pain that inevitably came with that, and in doing so, I had forced it and myself to be alive in unnatural ways.

For ten years, my ex-husband and I were two planets orbiting each other—day in and day out. I never thought we would have to live without each other. And even in the later years, despite all we’d been through, I was still in love with him and had great love for him.

Losing this love came with an immense level of pain—even worse that I thought.

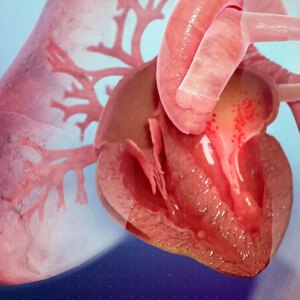

For six months I walked around feeling like my chest had been ripped open. The pain was not just a fleeting sensation; it was a tangible, daily presence in my life, so intense that by the time the afternoon came around, I could do nothing but lie down on my bedroom floor, the weight of the world pressing down on my chest. The pain was so dense and heavy it felt like it was squeezing the air from my lungs.

When things we love end or die, we experience pain. Pain and grief are the natural response to death, and to endings in general. But we also have a simple, biological tendency to cling to things that make us feel good and to avoid things that make us feel bad.

This is a paradox—pain is biologically natural, but we try to avert it. In averting it, we miss the point.

The Alchemy of Pain: Increased Resilience and Sensitivity

Pain and fear are so profound that they transform your understanding of life.

If we’re lucky, we don’t get a lot of opportunities for them over the course of our lives, but they are an important part of nature’s design.

The human organism evolves through many things, and pain is a very potent catalyst for our evolution. It makes our interior worlds wider and deeper in their capacity to understand and hold life, and the more pain we allow ourselves to feel, the bigger our tolerance for it grows.

What I came to feel, through the death and ending of my relationship, was more deeply in touch with the nature inside and all around me. It was as though the pain had entered into and worked out all the petrified spaces within me and brought renewed sensitivity back into my life.

Death and Endings are Not Tragedies

Death and endings are natural parts of life. To argue with them is like arguing with our need to eat—we only hurt ourselves. More importantly, we rob ourselves of the biological purpose these endings are here to serve.

I have learned to notice more closely when I’m stopping a death from occurring. I’ve learned to embrace the pain of endings, to love what they’ve done inside me—reshaping my life to bring me to new, more authentic, more deeply fulfilling places I never thought I’d be able to reach.

My deconstruction still hurts every day, but I am much less afraid of it now. I feel way more in partnership with my fear, and I can now recognize it as a healthy, normal part of my own psychology.

As I face life’s uncertainty, I know that when this immense level of pain comes again, I will feel it just as much, but the fear will be more tolerable. And I know now to take solace in the beauty and intention of its design—to grow my heart and soul in breadth and depth.

After a year, my divorce finally came through last week, and when I look around at my life, I realize I was right—not much remains. The people I surround myself with, where I spend my time, and even my business is different.

It will be a while before I can say my healing journey is complete, but as I continue to sink deep into my bones, to reclaim the parts of me that were lost these last few years, and re-learn how to dream my dreams alone, one thing above all else is clear: I am back in touch with everything inside me again, feeling all parts of my humanity and all parts of my life, and that’s all that matters.

About Rachel Browne

As the owner of Emergent Voice, Rachel Browne is a doula for existence. She guides individuals to fulfill their unique life potential by helping uncover their truth and materialize their gifts in the world. Through her existential approach, she facilitates self-discovery, knowledge, and becoming, helping shepherd people along the path of actualization. Get to know her by booking a free tea now at emergent-voice.com.

https://cdn.tinybuddha.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Woman-blowing-dandelion.png

2024-04-24 15:21:00