Technology Reporter

Reaction Engines

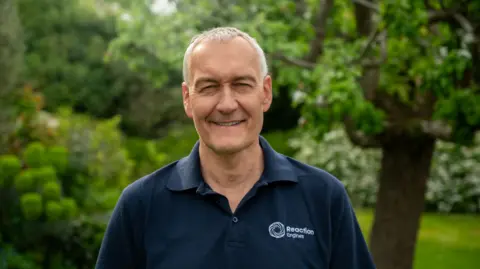

Reaction Engines“It was going great until it fell apart.” Richard Varvill recalls the emotional shock that hits home when a high-tech venture goes off the rails.

The former chief technology officer speaks ruefully about his long career trying to bring a revolutionary aerospace engine to fruition at UK firm Reaction Engines.

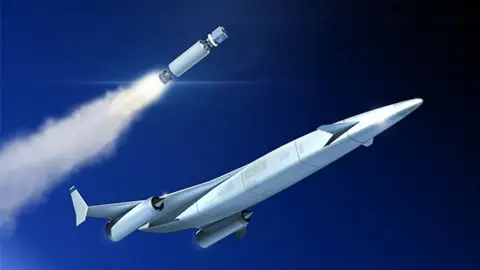

The origins of Reaction Engines go back to the Hotol project in the 1980s. This was a futuristic space plane that caught the public imagination with the prospect of a British aircraft flying beyond the atmosphere.

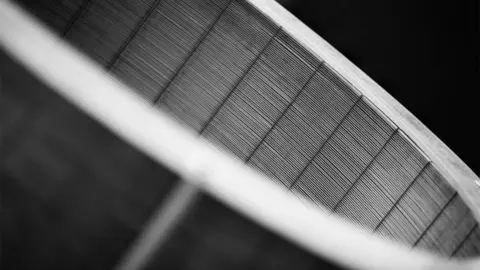

The secret sauce of Hotol was heat exchanger technology, an attempt to cool the super-heated 1,000C air that enters an engine at hypersonic speeds.

Without cooling this will melt aluminium, and is, Mr Varvill says, “literally too hot to handle”.

Fast forward three decades to October 2024 and Reaction Engines was bringing the heat exchanger to life at sites in the UK and US.

UK Ministry of Defence funding took the company into hypersonic research with Rolls-Royce for an unmanned aircraft. But that was not enough to keep the business afloat.

Rolls-Royce declines to go into details about Reaction’s collapse, but Mr Varvill is more specific.

“Rolls-Royce said it had other priorities and the UK military has very little money.”

Richard Varvill

Richard VarvillAviation is a business with a very long gestation time for a product. It can take 20 years to develop an aircraft. This unforgiving journey is known as crossing the Valley of Death.

Mr Varvill knew the business had to raise more funds towards the end of 2024 but big investors were reluctant to jump on board.

“The game was being played right to the very end, but to cross the Valley of Death in aerospace is very hard.”

What was the atmosphere like in those last days as the administrators moved in?

“It was pretty grim, we were all called into the lecture theatre and the managing director gave a speech about how the board ‘had tried everything’. Then came the unpleasant experience of handing over passes and getting personal items. It was definitely a bad day at the office.”

This bad day was too much for some. “A few people were in tears. A lot of them were shocked and upset because they’d hoped we could pull it off right up to the end.”

It was galling for Mr Varvill “because we were turning it around with an improved engine. Just as we were getting close to succeeding we failed. That’s a uniquely British characteristic.”

Reaction Engines Ltd

Reaction Engines LtdDid they follow the traditional path after a mass lay-off and head to the nearest pub? “We had a very large party at my house. Otherwise it would have been pretty awful to have put all that effort into the company and not mark it in some way.”

His former colleague Kathryn Evans headed up the space effort, the work around hypersonic flight for the Ministry of Defence and opportunities to apply the technology in any other commercial areas.

When did she know the game was up? “It’s tricky to say when I knew it was going wrong, I was very hopeful to the end. While there was a lot of uncertainty there was a strong pipeline of opportunities.”

She remembers the moment the axe fell and she joined 200 colleagues in the HQ’s auditorium.

“It was the 31st of October, a Thursday, I knew it was bad news but when you’re made redundant with immediate effect there’s no time to think about it. We’d all been fighting right to the end so then my adrenalin crashed.”

And those final hours were recorded. One of her colleagues brought in a Polaroid camera. Portrait photos were taken and stuck on a board with message expressing what Reaction Engines meant to individuals.

What did Ms Evans write? “I will very much miss working with brilliant minds in a kind, supportive culture.”

Since then she’s been reflecting “on an unfinished mission and the technology’s potential”.

But her personal pride remains strong. “It was British engineering at its best and it’s important for people to hold their heads up high.”

Her boss Adam Dissel, president of Reaction Engines, ran the US arm of the business. He laments the unsuccessful struggle to wrest more funds from big names in aerospace.

“The technology consistently worked and was fairly mature. But some of our strategic investors weren’t excited enough to put more money in and that put others off.”

The main investors were Boeing, BAE Systems and Roll-Royce. He feels they could have done more to give the wider investment community confidence in Reaction Engines.

It would have avoided a lot of pain.

“My team had put heart and soul into the company and we had a good cry. “

Did they really shed tears? “Absolutely, I had my tears at our final meeting where we joined hands and stood up. I said ‘We still did great, take a bow.”

What lessons can we draw for other high-tech ventures? “You definitely have no choice but to be optimistic,” says Mr Dissel.

The grim procedure of winding down the business took over as passwords and laptops were collected while servers were backed up in case “some future incarnation of the business can be preserved”.

The company had been going in various guises for 35 years. “We didn’t want it to go to rust. I expect the administrator will look for a buyer for the intellectual property assets,” Mr Dissel adds.

Other former employees also hold out for a phoenix rising from the ashes. But the Valley of Death looms large.

“Reaction Engines was playing at the very edge of what was possible. We were working for the fastest engines and highest temperatures. We bit off the hard job,” says Mr Dissel.

Despite all this Mr Varvill’s own epitaph for the business overshadows technological milestones. “We failed because we ran out of money.”

Leave a Reply