BBC

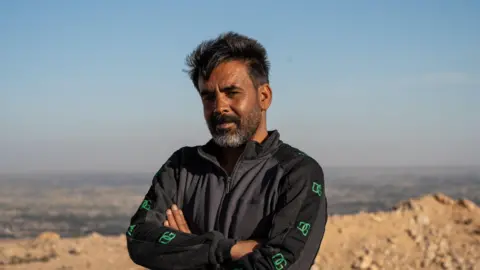

BBC“These,” says Dr Anas al-Hourani, “are from a mixed mass grave.”

The head of the newly-opened Syrian Identification Centre is standing next to two tables, covered in femurs. There are 32 of the human thigh bones on each laminated white tablecloth. They have been neatly aligned and numbered.

Sorting is the first task for this new link in the long chain from crime to justice in Syria. A “mixed mass grave” means that corpses were thrown one on top of another.

The chances are, these bones belong to some of the hundreds of thousands believed to have been killed by the regimes of the ousted president Bashar al-Assad and his father, Hafez, who together ruled Syria for more than five decades.

If so, says Dr al-Hourani, they were among the more recent victims: they died no more than a year ago.

Dr al-Hourani is a forensic odontologist: teeth can tell you so much more about a body, he says, at least when it comes to identifying who the person was.

But with a femur the lab workers in the basement of this squat grey office building in Damascus can begin the task: they can learn the height, the sex, the age, what sort of job they had; they might also be able to see whether the victim was tortured.

The gold standard in identification is of course DNA analysis. But, he says, there is just one DNA testing centre in Syria. Many were destroyed during the country’s civil war. And “because of sanctions, a lot of the precursor chemicals that we need for the tests are currently not available”.

They’ve also been informed that “parts of the instruments could be used for aviation and so for military purposes”. In other words, they could be deemed “dual use”, and so proscribed by many Western countries from export to Syria.

Add to that, the cost: $250 (£187) for a single test. And, says Dr al-Hourani, “in a mixed mass grave, you have to do about 20 tests to gather all the parts of one body”. The lab relies entirely on funding from the International Committee of the Red Cross.

The new government of Islamist rebels-turned-rulers says that what they call “transitional justice” is one of their priorities.

Many Syrians who have lost relatives, and lost all trace of them, have told the BBC that they remain unimpressed and frustrated: they want to see more effort from the people who finally chased Bashar al-Assad from power last December after 13 years of war.

During those long years of conflict, hundreds of thousands were killed, and millions displaced. And, by one estimate, more than 130,000 people were forcibly disappeared.

At the current rate, it can take months to identify just one victim from a mixed mass grave. “This,” says Dr al-Hourani, “will be the work of many, many years.”

‘Mangled and tortured’ bodies

Eleven of those “mixed mass graves” are slung around a beautiful, barren hilltop outside Damascus. The BBC are the first international media to see this site. The graves are quite visible now. In the years since they were dug, their surface has sunk into the dry, stony earth.

Accompanying us is Hussein Alawi al-Manfi, or Abu Ali, as he also calls himself. He was a driver in the Syrian military. “My cargo,” says Abu Ali, “was human bodies.”

This compact man with a salt and pepper beard was tracked down thanks to the tireless investigative work of Mouaz Mustafa, the Syrian-American executive director of the Syrian Emergency Task Force, a US-based advocacy group. He had persuaded Abu Ali to join us, to bear witness to what Mouaz calls “the worst crimes of the 21st Century”.

Abu Ali transported lorry loads of corpses to multiple sites for more than 10 years. At this location, he came, on average, twice a week for roughly two years at the start of the demonstrations and then the war, between 2011 and 2013.

The routine was always the same. He’d head to a military or security installation. “I had a 16m (52ft) trailer. It wasn’t always filled to the brim. But I’d have, I guess, an average of 150 to 200 bodies in each load.”

Of his cargo, he says he is convinced they were civilians. Their bodies were “mangled and tortured”. The only identification he could see were numbers written on the cadaver or stuck to the chest or forehead. The numbers identified where they had died.

There were a lot, he said, from “215” – a notorious military intelligence detention centre in Damascus known as “Branch 215”. It is a place we will re-visit in this story.

Abu Ali’s trailer did not have a hydraulic lift to tip and dump his load. When he backed up to a trench, soldiers would pull the bodies into the hole one after another. Then a front-loader tractor would “flatten them out, compress them in, fill in the grave.”

Three men with weathered faces from a neighbouring village have arrived. They corroborate the story of the regular visits by military lorries to this remote spot.

And as for the man behind the wheel: how could he do this for week after week, year after year? What was he telling himself each time he climbed into his cab?

Abu Ali says he learned to be a mute servant of the state. “You can’t say anything good or bad.”

As the soldiers dumped the corpses into the freshly excavated pits, “I would just walk away and look at the stars. Or look down towards Damascus.”

‘They broke his arms and beat his back’

Damascus is where Malak Aoude has recently returned, after years as a refugee in Turkey. Syria may have been freed of the chokehold of the Assads’ dynastic dictatorship. Malak is still serving a life sentence.

For the past 13 years, she has been locked into a daily routine of pain and longing. It was 2012, a year after some of the people of Syria had dared to raise a protest against their president, that her two boys were disappeared.

Mohammed was still a teenager when he was conscripted into Assad’s army, as the demonstrations spread and the regime’s deadly crackdown sparked a full-blown war.

He hated what he was seeing, his mother says. Mohammed started absconding, and even went on the demos himself. But he was tracked down.

“They broke his arms and beat his back,” says his mother. “He spent three days unconscious in hospital.”

Mohammed went AWOL again. “I reported him missing,” says Malak. “But I was hiding him.”

In May 2012, 19-year-old’s Mohammed luck ran out. He was caught along with a group of friends. They were shot. Malak says there was no formal notification. But she has always assumed he was killed.

Six months later, Mohammed’s younger brother Maher was dragged from school by officers. It was Maher’s second arrest. He’d gone to the protests in 2011, aged 14. That had led to his first arrest. When he was let out of detention, a month later, he was in his underwear, covered, says his mother, in cigarette burns, wounds and lice. “He was terrified.”

Malak thinks Maher was disappeared from school in 2012 because the authorities had found that she had been hiding his older brother. Now, for the first time in 13 years, Malak returns to that school, desperate to get any clue about what happened to Maher.

The new headteacher produces a couple of battered red ledgers. Malak traces the rows of names with her finger, and then finds her son’s name. December 2012, the record flatly states: Maher has been excluded from school because he has failed to turn up for lessons for two weeks.

There is no explanation that it is the state which has disappeared him. There is something else, though: a folder with Maher’s school records has been found. Its cover is adorned with a photograph of a wise Bashar al-Assad, gazing thoughtfully into the distance. Malak picks up a pen from the headteacher’s desk and scribbles over the photo. Six months ago, that gesture could have been lethal.

For years, the only scraps Malak had to cling to were two men who say they saw Maher in “Branch 215” – that same military detention centre which produced so many corpses for Abu Ali to transport.

One of the witnesses told Malak that her boy had told him something about his parents that, his mother says, only he could have known. It was definitely him. “He asked this man to tell me he was doing fine.” Malak heaves and leaks tears, stuffs a tattered tissue into the corners of her eyes.

For Malak, like so many Syrians, the fall of Assad was not just a day of joy, but of hope. “I thought there was a 90% chance Maher would walk out of prison. I was waiting for him.”

But she has not even been able to find her son’s name on the prison lists. And so the throb of pain continues to course through her. “I feel lost and confused,” she says.

Her own younger brother, Mahmoud, had been killed by a tank firing on civilians in 2013.

“At least he had a funeral.”

Leave a Reply