Australia correspondent

Getty Images

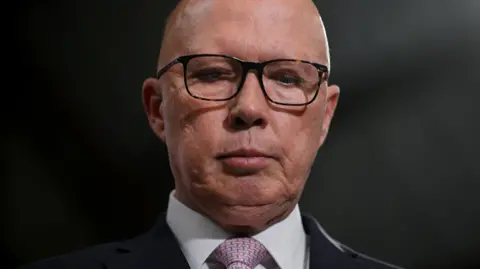

Getty Images“It’s not our night,” Australia’s opposition leader Peter Dutton told a roomful of supporters in Brisbane after his rival, Anthony Albanese, was re-elected as prime minister.

It was indeed a bruising night for Dutton, a 54-year-old political veteran who also lost his parliamentary seat of 24 years to a candidate from Albanese’s Labor Party.

This is a big win for the prime minister, who made a surprising comeback to secure a comfortable majority for a second term. But it’s an even bigger loss for Dutton and his Liberal National Coalition.

Dutton initially seemed to have an advantage over the incumbent PM who was battling a cost-of-living crisis and dismal ratings. But that advantage vanished as the campaign wore on, ending in a humiliating defeat.

An awkward and inconsistent campaign that did not do enough to reassure voters was partly to blame. But there is no mistaking the big part played by what some have called the “Trump effect”.

Dutton, whether he liked it or not, was a man who many saw as Australia’s Trump – but as it turns out Australians do not appear to want that.

The Trump factor

Dutton’s brand of hard-line conservatism, his support for controversial immigration policies – like sending asylum seekers to offshore detention centres – and his fierce criticism of China, all led to comparisons with US President Donald Trump.

It’s a likeness he has rejected but then the Coalition pursued policies that seemed to have been borrowed from the Trump administration.

Dutton said that if elected he would cut public sector jobs – more than 40,000 by some estimates. This reminded voters of billionaire Elon Musk’s Doge, or Department of Government Efficiency, which has slashed US bureaucracy. Dutton later walked back the plan.

The Coalition even appointed Jacinta Nampijinpa Price as shadow minister for government efficiency. And images of her wearing a cap with the words Maga – short for the popular Trump slogan, Make America Great Again – have became a key talking point.

Getty Images

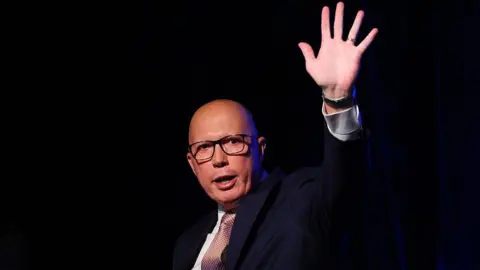

Getty ImagesNone of this served Dutton well and he knew it. Towards the end of the campaign, he tried to shake off Trump’s shadow, and in the final leaders’ debate he repeatedly told the audience that he didn’t know Trump before attempting to answer questions on him.

“The Coalition will probably regret issuing messages that came across as supporting Trump and opposing the US Democrats,” said Frank Mols, a political science lecturer at the University of Queensland.

“Once the stock markets started to drop in response to the uncertainty created by the [Trump’s] tariffs, it became harder for the Coalition to profile itself as a safer pair of hands for the economy.”

The talk of trade wars and tariffs increased voters’ worries. Speaking to people across Australia – the BBC travelled to Perth in Western Australia and Melbourne in the final week of campaigning – it was clear that global politics only became more important through the campaign.

Australia has long balanced its military alliance with the US and its economic relationship with China, its biggest trading partner.

But a US-China trade war, along with an unpredictable White House, is tricky territory for any country – even a US ally like Australia.

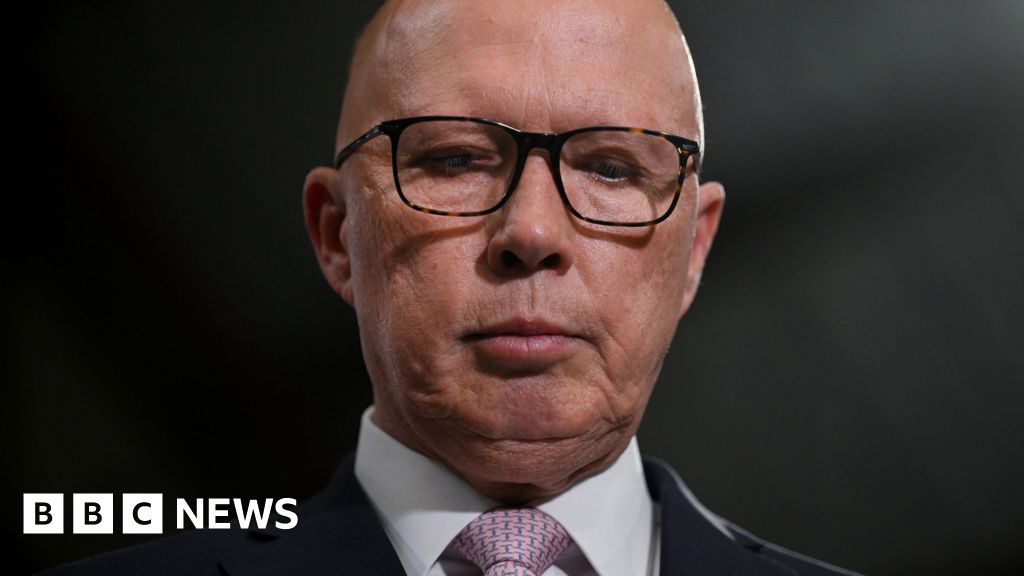

Could Dutton provide stability in these unusual times?

Dutton had long tried to convince voters that he would be the politician best suited to dealing with Trump. He often cited his experience as a cabinet minister during tariff negotiations in Trump’s first term.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut in the end voters weren’t convinced.

Dutton’s own inconsistent policies and the Trump-esque rhetoric and decisions appear to have driven away an electorate that is deeply concerned about a new, tumultuous world order.

“Our message was confusing… Labor had a tight and very disciplined campaign,” Jitendra Prasad, a LNP supporter, told the BBC as he was about to leave the watch party on Saturday night after a disappointing outcome.

That was evident in the swings towards Labor across the country, which led to a fairly quick, emphatic result.

Towards the end of the campaign, Dutton also embraced the right-wing One Nation Party, which some Coalition members had warned was the wrong move. And it didn’t seem to have helped. Rather, it may have hurt him.

“They just read the rooms incorrectly,” says Ben Wellings, associate professor of Politics and International Relations at Monash University.

“It was one of the things that we always say about the electorate in Australia – it’s a small C conservative and maybe the radical right message was just in the end, too radical and seemed too disruptive.”

An inconsistent campaign

What also didn’t help was that Dutton’s was never a smooth campaign.

There were gaffes, such as when he accidentally hit a cameraman with a football, and costly missteps, like getting the price of a carton of eggs wrong during an election debate – his guess (A$4.20) was, in fact, half the actual price.

It was not a good look in an election where cost-of-living has been a dominant theme.

“Dutton has seemed more comfortable attacking Labor than presenting a strong alternative,” says Jacob Broom, a lecturer in politics and policy at Murdoch University in Perth.

“I think it has been effective for Labor to point to the Liberals voting against cost-of-living measures like the tax cuts which they proposed toward the end of the term.”

While Dutton criticised Labour’s tax relief measures and spending, he then announced that he would also effect tax rebates and big spends, including billions to boost defence and fix an ailing public healthcare system.

But at the same time he also promised cuts. Analysts say this inconsistency confused voters and became an unfortunate theme in his campaign.

He announced and then walked back plans for huge changes to the bureaucracy, including job cuts and the plans to end work from home arrangements. He said it was “a mistake”.

But “the backflips on working from home and his uncertainty over public service cuts,” complicated his message, according to John Warhurst, Emeritus Professor, Australian National University.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe result, many believe, was the lack of a coherent campaign.

“I think people couldn’t understand Dutton’s policies,” a member of Dutton’s own party in his Dickson constituency told the BBC earlier on Saturday.

He wondered if Dutton’s support for nuclear energy put people off – an issue that analysts such as Dr Mols said could have worked against him because Australian voters had not “warmed up” to the idea of nuclear energy.

Ultimately, the biggest issue this election – cost-of-living – may have helped Labor cement its message that theirs was the steadier hand.

Evanthia Smith, another voter in Dutton’s Dickson seat, said she voted for Labor because she believed their candidate would do more to improve public education and access to healthcare.

Dutton acknowledged the huge loss the Coalition had faced: “Our Liberal family is hurting across the country tonight, including in my electorate of Dickson… We’ll rebuild from here.”

It was the same advice a supporter in Brisbane had for the party: “The party needs to go back to the drawing block and look at their policies. We need to focus on the typical issues: Housing, cost-of-living – they are the biggest.”

Leave a Reply