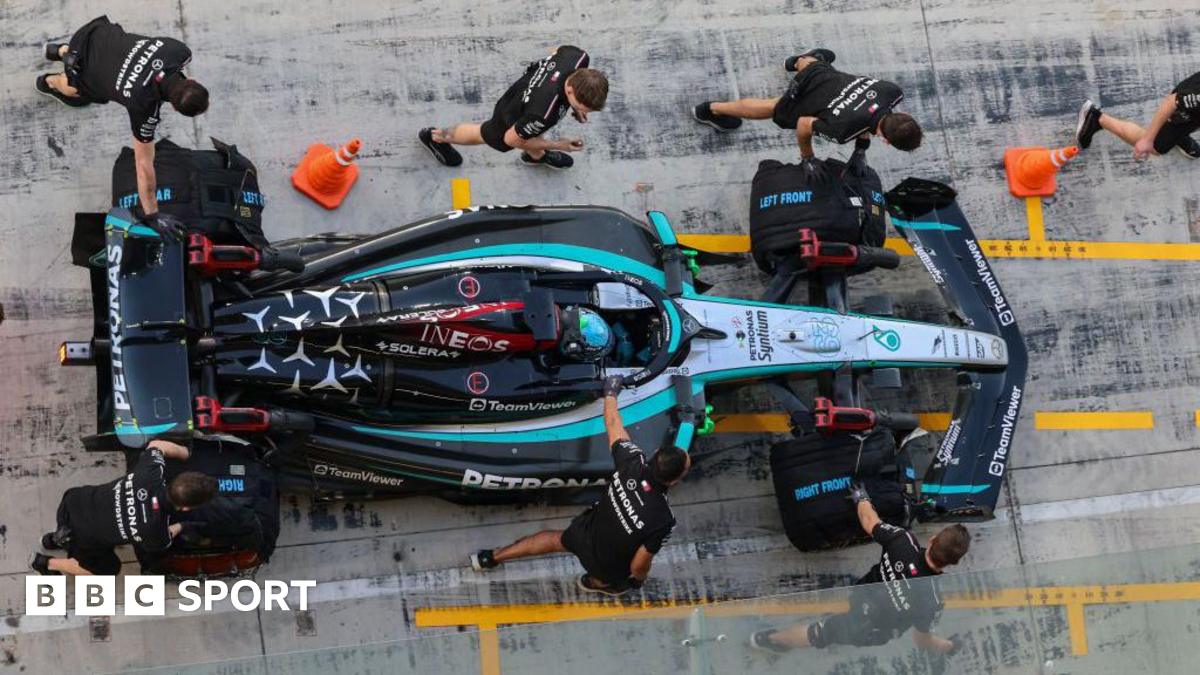

Formula 1 bosses have agreed in principle to a mechanism that would allow engine manufacturers facing a performance shortfall under next year’s new rules to catch up.

But there was no agreement at a meeting of the F1 Commission on Thursday on a proposal to cut the amount of electrical energy permitted in races.

That had been tabled as a means of preventing cars running out of electrical deployment down the straights at certain circuits.

Both ideas will be discussed at future meetings of the F1 power-unit manufacturers.

It was broadly agreed by the F1 Commission that the regulations, which are scheduled to run from 2026-30, should be modified so that it is easier for any manufacturer whose engine is short of performance to close the gap to its rivals.

The new rules for next year retain 1.6-litre turbo hybrid engines but with a simplified architecture while increasing the proportion of power supplied by the electrical part of the engine to about 50% from the current 20%, and running on sustainable fuels.

There are concerns that the greater demands on the hybrid system could lead to significant performance differences between the various manufacturers – in 2026, Red Bull Powertrains and Audi join current suppliers Mercedes, Ferrari and Honda in the sport.

Mercedes, Honda and Audi made clear at a meeting at the Bahrain Grand Prix earlier this month that they felt the sport should stick to the rules as they are and retain the electrical part of the engine as a potential performance differentiator.

The increased hybrid aspect of the rules was critical in attracting Audi and Red Bull’s partner Ford, and in convincing Honda to stay in F1. It has also persuaded General Motors to enter F1.

GM will run a Cadillac-branded new team next year using Ferrari engines and has pledged to have its own power-unit ready by 2029.

The Bahrain meeting also kicked into the long grass a proposal to change the engine formula before 2030, although discussions will continue on this idea.

On Thursday, no agreement was reached on the details of mechanisms by which manufacturers may be able to make up a shortfall.

However, examples of ideas by which this could happen are to allow increased amounts of dynamometer testing or an increased engine budget cap to any who end up behind.

This has been passed to the power-unit working group for further refinement.

Leave a Reply