BBC Burmese

BBC

BBCAbout 15 children’s backpacks lie torn apart in the rubble – pink, blue and orange bags with books spilling out of them.

Spiderman toys and letters of the alphabet are scattered among broken chairs, tables and garden slides at the remains of this preschool destroyed by the huge earthquake that hit Myanmar on Friday.

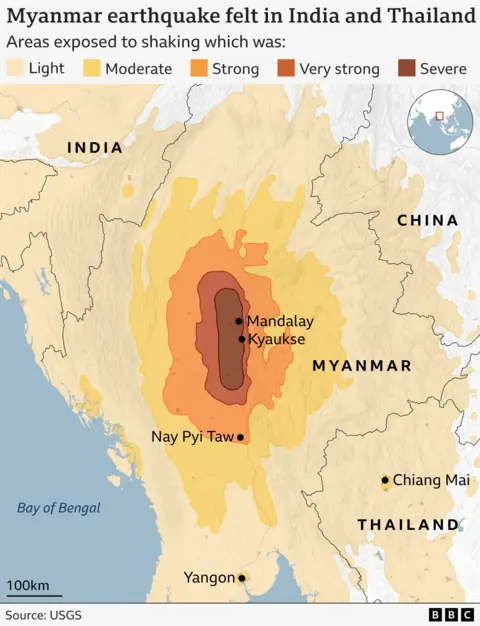

It is in the town of Kyaukse, about 40km (25 miles) south of Mandalay, one of the areas hit hardest by the 7.7 magnitude quake that killed at least 2,000 people.

Kywe Nyein, 71, weeps as he explains that his family are preparing to hold the funeral of his five-year-old granddaughter, Thet Hter San.

He says her mother was having lunch when the devastating earthquake began. She ran to the school, but the building had collapsed completely.

The little girl’s body was found about three hours later. “Fortunately, we got our beloved’s body intact, in one piece,” he says.

Locals say there were about 70 children, aged between two and seven, at the school on Friday, learning happily. But now there is little left except a pile of bricks, concrete and iron rods.

The school says 12 children and a teacher died, but locals believe the number is at least 40 – that is how many were in the downstairs section that collapsed.

Residents and parents are distraught. People say the whole town came to help with the rescue work and several bodies were retrieved on Friday. They describe mothers crying and calling out the names of their children long into the night.

Now, three days later, the site is quiet. People look at me with grief etched on their faces.

Aid groups are warning of a worsening humanitarian crisis in Myanmar, with hospitals damaged and overwhelmed, though the full scale of devastation is still emerging.

Before we arrived in Kyaukse, we had been in the capital, Nay Pyi Taw.

The worst-hit area we saw there was a building that had been residential quarters for civil servants. The whole ground floor had collapsed, leaving the three upper floors still standing on top of it.

There were traces of blood in the rubble. The intense stench suggested many people had died there, but there was no sign of rescue work.

A group of policemen were loading furniture and household goods on to trucks, and appeared to be trying to salvage what was still useable.

The police officer in charge would not give us an interview, though we were allowed to film for a while.

We could see people mourning and desolate, but they did not want to speak to the media, fearing reprisals from the military government.

We were left with so many questions. How many people were under the rubble? Could any of them still be alive? Why was there no rescue work, even to retrieve the bodies of the dead?

Just 10 minutes’ drive away, we had visited the capital’s largest hospital – known here as the “1,000-bed hospital”.

The roof of the emergency room had collapsed. At the entrance, a sign saying “Emergency Department” in English lay on the ground.

There were six military medical trucks and several tents outside, where patients evacuated from the hospital were being cared for.

The tents were being sprayed with water to give those inside some relief from the intense heat.

It looked like there were about 200 injured people there, some with bloodied heads, others with broken limbs.

We saw an official angrily reprimanding staff about other colleagues who had not turned up to work during the emergency.

I realised the man was the minister for health, Dr Thet Khaing Win, and approached him for an interview but he curtly rejected my request.

On the route into the city, people sat clustered under trees on the central reservation of the highway, trying to get some relief from the hot sun.

It is the hottest time of year – it must have been close to 40C – but they were afraid to be inside buildings because of the continuing aftershocks.

We had set out on our journey to the earthquake zone at 4am on Sunday morning from Yangon, about 600 km (370 miles) south of Mandalay. The road was pitch black, with no street lights.

After more than three hours’ driving, we saw a team of about 20 rescue workers in orange uniforms, with logos on their vests showing they had come from Hong Kong. We started to find cracks in the roads as we drove north.

The route normally has several checkpoints, but we had travelled for 185km (115 miles) before we saw one. A lone police officer told us the road ahead was closed because of a broken bridge, and showed us a diversion.

We had hoped to reach Mandalay, Myanmar’s second-largest city, by Sunday night.

But the diversion, and problems with our car in the heat, made that impossible.

A day later, we have finally reached the city. It is in complete darkness, with no street lights on and homes without power or running water.

We are anxious about what we will find here when morning comes.

Leave a Reply