BBC News

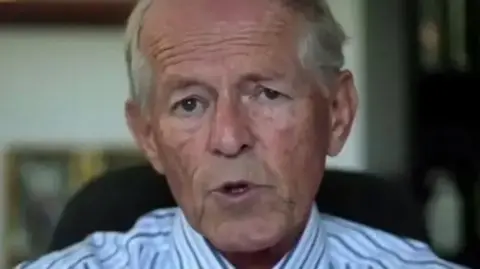

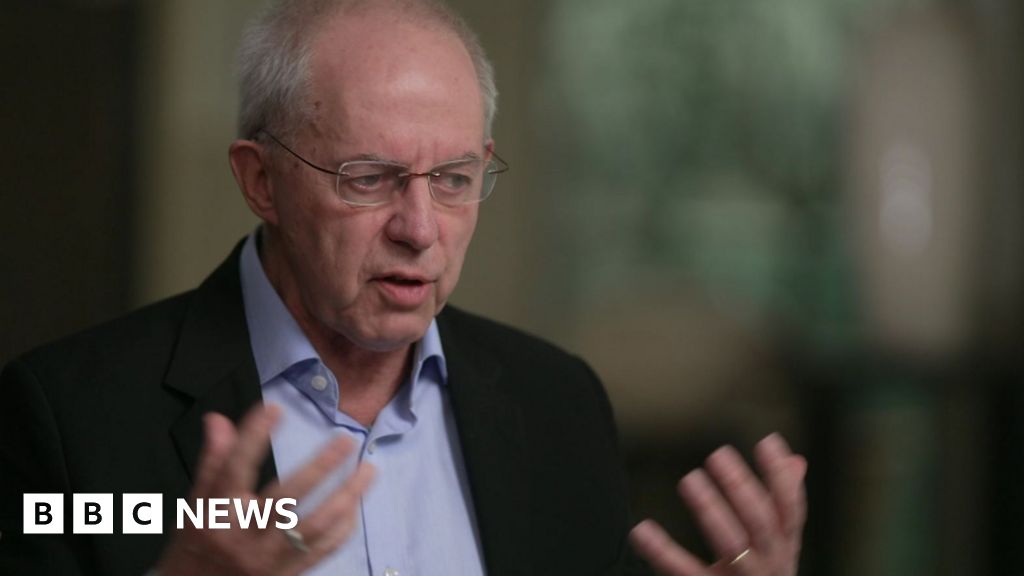

Justin Welby has told the BBC he forgives a serial abuser at the heart of a scandal that led to his resignation as Archbishop of Canterbury.

In his first interview since quitting in November last year, Welby said his forgiveness of John Smyth – arguably the most prolific abuser associated with the Church of England – was “irrelevant” and it was more important to help victims “rebuild their lives”.

Smyth, who died in 2018, attacked more than 100 boys and young men in the UK and Africa over decades.

A damning 2024 review found Welby “could and should” have done more to bring Smyth to justice, which the former archbishop said he feels a “deep sense of personal failure” over.

Speaking to the BBC’s Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg, Welby said there had been “absolute failure” on Smyth and:

- Said he was “profoundly ashamed” of a speech he gave shortly after resigning where he had made light of his exit

- Expressed frustration at not being able to get the Church’s governing body to introduce fully independent safeguarding or equality for women and gay couples

- Said it would be a “tragedy” for the Church to split between England and other parts of the Anglican communion

- Warned an increasingly diverse UK must create a “cohesive” society

Forgiveness

From the 1970s onwards, Smyth was a prominent figure in a Church-linked movement, and used his position to inflict sustained beatings for his own sexual gratification on boys and young men he would prey on at Christian camps and schools.

Smyth, who later lived in Zimbabwe and South Africa, continued to abuse after he left UK. But he never faced justice in the UK or abroad before he died, aged 77.

The 2024 Makin Report said his “brutal abuse” was “on an industrial scale” and concluded opportunities to investigate Smyth over his abuse were missed – including when evidence was presented to Welby in 2013.

Asked by the BBC if he would forgive Smyth, Welby said: “Yes. I think if he was alive and I saw him, but it’s not me he’s abused.

“He’s abused the victims and survivors. So whether I forgive or not is, to a large extent, irrelevant.”

Welby said it was more important for victims to be “cared for… liberated to rebuild their lives” by the Church than to speak about forgiveness.

Pressed on how victims might react, Welby said he would never suggest they should also forgive.

Asked whether he wanted to be forgiven by Smyth’s victims, Welby said: “Everyone wants to be forgiven but to demand forgiveness is to abuse again.”

While absolution is central to Welby’s lifelong faith, his forgiveness of Smyth may sit uncomfortably with some survivors, who have accused him of failing to engage with them.

One of Smyth’s victims, known as Graham – who made the 2013 complaint – told the BBC he would not forgive Welby.

He said: “I’ve said before that, if in 2017 he had contacted us, said ‘I will come and apologise to you personally, I am sorry, I messed up’, I would have forgiven him immediately – but he never has in those terms.”

Asked if he could ever forgive Welby, Graham said: “Not if he continues to blank us and refuses to tell us the truth. We’re the victims, we deserve to know what happened and we don’t yet.”

‘Profoundly ashamed’

Welby first met Smyth in the late 1970s at a Christian camp but has always insisted he did not become aware of any abuse allegation against Smyth until 2013.

The Makin Report said that was “unlikely”, even if the full picture was still unclear to Welby.

Asked about that finding, Welby said: “You can believe it or not, I did not have a clue.”

Pushed on why he did not do more while in office, Welby said police told him “under no circumstances are you to get involved because you will contaminate our enquiry”.

He added: “I should have pestered them to be honest, and I see that now.”

Earlier in the interview, Welby told the BBC he was “absolutely overwhelmed” by the scale of abuse allegations within the Church.

He said: “I didn’t do the job on safeguarding… We’re meant to be shepherds of the flock, that’s one of the expressions Jesus uses… and I failed on that.”

It took several days for Welby to resign after the report was published, at which point he accepted “personal and institutional responsibility”.

Asked about his initial decision not to quit, Welby said he was “caught out” when the report’s findings appeared earlier than expected, and had “not really thought it through”, before deciding he should resign out of respect for victims.

Pressed on whether he had been pushed out, Welby said: “I made that decision for myself. I didn’t much look at the papers, so it wasn’t that. It was recognising absolute failure on Smyth.”

Welby caused further controversy in December 2024 when he was accused of making light of the Church’s abuse crisis during a House of Lords speech, comments victims said left them “dismayed” and “disgusted”.

He said he was “profoundly ashamed” of the speech and “wasn’t in a good space at the time,” adding: “It’s one of those moments where, when I think of it, I just wince. It was entirely wrong and entirely inexcusable.”

Where next for the Church?

Last month, the General Synod – the Church’s governing body – rejected a proposal that would have made safeguarding fully independent, which proponents say would increase accountability but critics say would delay reform.

Welby told the BBC he is “entirely in favour” of independent safeguarding but could not convince the Synod to adopt it. The Archbishop, he said, “is not the chief executive of the Church of England PLC – you can’t make this change by saying, ‘this will now happen’.”

Welby also expressed frustration at the Synod’s refusal to grant greater equality for gay couples and female clergy.

He told the BBC: “I would have loved to be able to wave a magic wand and get it all right… but that isn’t the reality and I didn’t have the votes.”

Asked whether the cultural divides in a global church of 85 million people could lead to a split, Welby said: “I can see it happening. I think it would be a total tragedy because when families split it always leaves huge damage for everyone.”

The 2021 census in England and Wales found less than half of the population described themselves as Christian for the first time ever, while Muslim and Hindu populations increased, although Welby pointed out the Church has “grown over the last few years”.

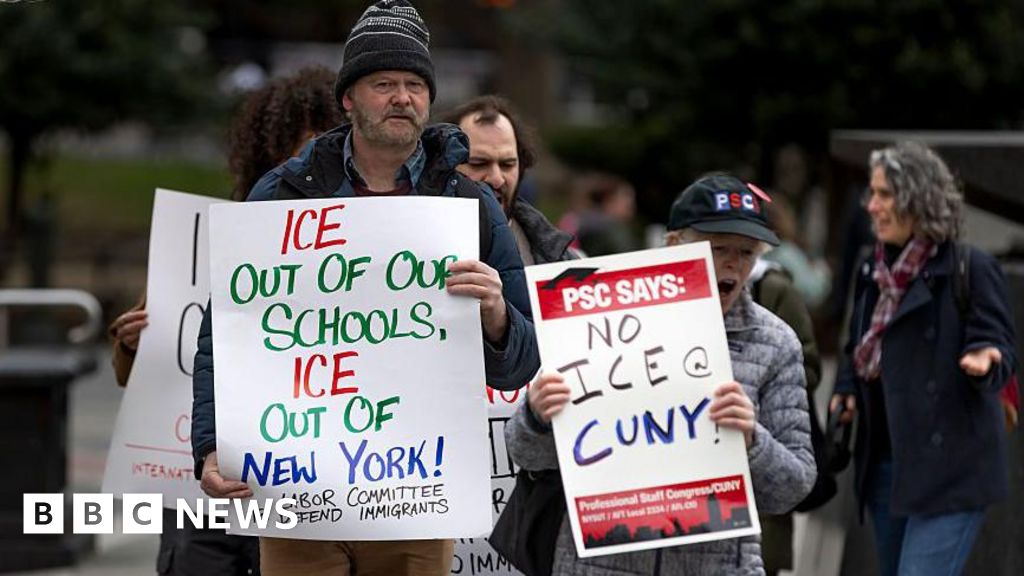

Welby said generating “social cohesion” is set to be the country’s “biggest challenge”.

“Whether you are in favour or against, or neutral, we are now certainly in the top two or three, possibly the most diverse nation on Earth… that has happened in half a century and the challenge of that is working out who we are,” he said.

“People want a cohesive society. They want a society where we know who we are and what we value and where we’re going – and this is where the Church plays its role.”

Responding to Welby’s interview, a Church of England spokesperson said it would be “a reminder to Smyth survivors of their awful abuse and its lifelong effects”.

They repeated the Church’s apology to victims and said anyone who comes forward “will be heard and responded to carefully and compassionately by safeguarding professionals”.

A statement continued: “In the past 10 years, the Church has developed and strengthened its safeguarding policies and practices, making significant improvements in training, national safeguarding standards and external audits, and continues to do so.”

Watch more of the exclusive interview on Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg.

The full interview will be on iPlayer and BBC Sounds from 09:00, and BBC 2 on Sunday at 23:35.

Leave a Reply