BBC News

Stephen Fildes / BBC

Stephen Fildes / BBC“I just burst out crying,” says Brian Buckle, recalling the moment he read the rejection letter from the Ministry of Justice after applying for compensation.

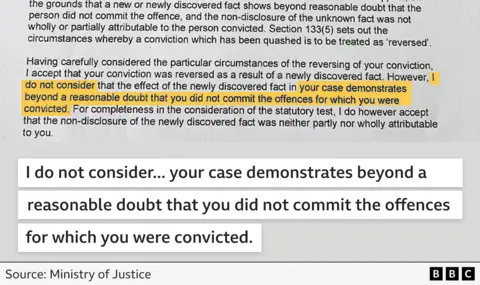

It said it accepted Brian was “innocent” of the sexual offences he had been wrongly imprisoned for, but he had failed to prove “beyond a reasonable doubt” that he had not committed the crimes.

Brian had been completely cleared of the sex abuse charges he had been jailed for in 2017.

A five-year legal battle had culminated in the Court of Appeal finding his conviction unsafe. Brian’s legal team produced a detailed defence including new witnesses and fresh forensic evidence, at a three-week retrial in 2022. The jury unanimously returned a verdict of “not guilty” in just over an hour.

During the struggle to clear his name, Brian used savings and family loans to pay for his legal fees – totalling £500,000. This is equal to the total amount of compensation that Brian was able to apply for.

The letter from the Ministry of Justice came nearly a year after he first submitted his application. The assessor, who had never spoken to Brian or his legal team, said he wasn’t eligible for a pay-out because there was not enough proof that he had hadn’t carried out the offences.

“What do I need to do to prove that I’m an innocent person?” says Brian. “I’ve lost five years of my life, my job, my pension. People are absolutely gobsmacked when you tell them I’ve been refused compensation.”

The Ministry of Justice told the BBC it acknowledges the “grave impact of miscarriages of justice” and is “committed to supporting individuals in rebuilding their lives”.

For hundreds of years it has been accepted that someone is presumed innocent until a court of law finds them guilty.

However, following a small but significant law change in 2014, if a victim of a miscarriage of justice in England and Wales wants to receive compensation, they must not only be cleared, but also demonstrate they are innocent – in effect “reversing the burden of proof”, according to Brian’s barrister, Stephen Vullo KC.

“It’s an almost impossibly high hurdle over which very few people can jump,” he says.

Stephen Fildes / BBC

Stephen Fildes / BBCAbout 93% of applications for compensation have been rejected by the Ministry of Justice since 2016, government figures show.

Mr Vullo believes the legislation change was designed so that money would not be paid out. “It’s not by accident, it’s by design,” he says.

The current system is “inhuman” and “cruel” says Suzanne Gower, a former criminal defence solicitor and specialist in miscarriages of justice at the University of Manchester. She believes it sends a message that the state doesn’t accept responsibility when it causes harm.

Several legal experts told us the special compensation schemes set up by the government for victims of the Post Office scandal were “a tacit admission” that the existing system is “unfair” and not working.

Ms Gower says while sub-postmasters wrongly prosecuted for theft and fraud deserve “every penny for what they’ve been through” they were only able to claim compensation after the TV drama about the case generated so much public pressure for action.

Mr Vullo says it is unfair to less-publicised cases if the government’s approach is driven by a fear of being embarrassed.

“The system should be set up fairly so that everybody receives compensation,” he tells us.

Stephen Fildes / BBC

Stephen Fildes / BBCIntroducing the law change in 2014, the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition government argued it would stop compensation going to people who only had their conviction quashed on a technicality, and therefore might be guilty.

But Lewis Ross, who specialises in legal and political philosophy at the London School of Economics, says this was achieved at the expense of innocent people who had been falsely imprisoned.

“There does need to be some standard for compensation,” says Mr Ross. “It’s just curious the government picked the most demanding one.”

There are now growing calls for the 2014 law to be reversed so a person would only need to show they had been a victim of a miscarriage of justice to receive compensation.

That is the system still used in Scotland, Northern Ireland and most of the rest of Europe.

The Law Commission is currently compiling a review for the government on how to reform the criminal appeals system in England and Wales, which includes compensation for victims of miscarriages of justice.

It also acknowledges that the current legislation is too severe and has provisionally proposed that claimants could still be asked to prove their innocence, but be expected to meet a lower evidential threshold.

The government says it will need to consider the commission’s findings, due to be released in 2026, before deciding how to act.

Stephen Fildes / BBC

Stephen Fildes / BBCBrian, who is from Pembrokeshire, now has the support of his local MP – Ben Lake – who will host a debate at Westminster. Mr Lake says he was “appalled” after hearing about Brian’s case.

“Sadly, miscarriages of justice happen. They always have and they always will,” he says. “But when we have a situation where an individual has been incarcerated for whatever reason for incorrect evidence or incorrect judgements, we should ensure that they are compensated for that.”

Any law change should be made retrospectively so the Buckle family could benefit, Mr Lake adds.

Brian describes the help from his MP as a “step forward”, not just for him but for other victims of a miscarriage of justice.

“I’m definitely not the old Brian Buckle,” he says. “I can’t keep a job down because my head is all over the place. Every single night all I dream about is being in prison or trying to get out of prison.”

The events of the past few years have taken their toll, not only on Brian – who has been formally diagnosed with PTSD – but also on his family.

His daughter Georgia says she suffered from suicidal thoughts during her father’s imprisonment.

After an eight-year ordeal, Brian believes there needs to be change to a “broken” justice system. He says he would like an apology, and some recognition that the authorities made a mistake.

“I will take what happened to me to the grave,” he says. “Money is not going to change how I am mentally, but it’s the principle of the justice system admitting that they got it wrong.”

Leave a Reply