BBC

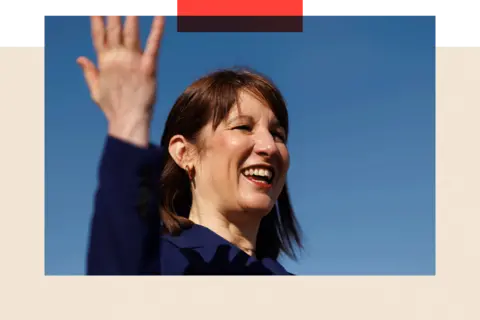

BBCThe prime minister has just had another moment at the lectern, urging Europe to stand up for Ukraine. He’s an increasingly confident leader, but in the coming days No 10 faces what could be a defining fight at home.

“There is a collision coming,” a Labour insider tells me. Sir Keir Starmer has long been up for fights with his party. But with controversy around every corner, who are the tribes in the party in 2025, and might they fight back?

The party’s history is crammed with bitter bust-ups, years when MPs seemed most comfortable to be fighting each other, rather than political rivals.

With a squeeze on benefits coming, there is unease on the back, and the front benches, including in cabinet. The decision on winter fuel payments still causes resentment, and new plans for immigration coming in a white paper later in the spring are likely to be controversial too.

A long-time party observer says: “Put three Labour people in a room and you’ll have a faction.”

Sir Keir’s allies seem pretty confident Labour’s ditched that habit of constant scrapping. But No 10 is worried enough to be inviting MPs into Downing Street to make their pitch for the changes to welfare, knowing there’ll be upset from the usual suspects and hoping there won’t be too much of a backlash on the soft left.

It’s also grappling with the massive group of MPs elected last year, with some eager backbenchers actively trying to make Sir Keir’s case, unkindly branded by one source as “toadies” trying to suck up to the leadership.

So how will the “usual suspects”, the “softies”, the “newbies” and the “toadies” shake down?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere has always been criticism of Sir Keir from the left-hand edge of Labour, not least because he spent the first couple of years in charge squeezing out the hard left, and even kicked out some MPs after the general election for voting against him over the cap on benefits for families with more than two children.

It’s common for MPs like Diane Abbott or Nadia Whittome to take pot shots at the prime minister’s plans. But now this group is much smaller and less influential than it once was, it can’t do much damage on its own. Gone are the days when the Socialist Campaign Group held sway with Jeremy Corbyn – there are only 23 MPs in the group these days. But unhappiness about the coming welfare cuts spreads its tentacles far further.

One of those arguing against them told me the vast majority of Labour MPs were in the “group of resistance” – and “privately some of the cabinet are very against it.”

There is a whiff of opportunity to force Sir Keir to back down, some believe. “There is a chance that the old left and the soft left come together,” another MP tells me.

A source on the left of the party tells me there’s “potential to broaden this out and team up with people who don’t want to see benefits cut after 15 years of austerity. The challenge for us on the left is to work with those people – then we’ll have a sizeable rebellion.” It is “breathtaking” to see new MPs backing undisclosed changes to benefits for disabled people, they add.

They point to the rebellion against Tony Blair in 1997 when 47 Labour MPs voted against the new government over – you guessed it – cuts to benefits. One hundred MPs abstained. It didn’t change the policy, just as a rebellion of that kind of size wouldn’t change it this time either, given the PM’s huge majority. But it shocked ministers, still in the pomp of their massive victory that year. Could this do the same?

Downing Street evidently is worried – but the resistance on the soft left so far seems, well, rather soft.

Shutterstock

ShutterstockAnother source tells me there are lots of colleagues who are expressing discomfort, and there are fault-lines, but it’s not organised. Some of those who would rather like there to be a rebellion seem to also rather like the idea of someone else organising it.

Rebellions do need organising, effort, energy, and an eagerness to make sparks fly. They also need leaders willing to put their head above the parapet. While the concern is strong, the appetite for a big spat when the plans eventually get to Parliament is less so, at least for now.

It’s symbolic of where power is held in the party right now. “The soft left has been obliterated,” a senior Labour figure tells me, adding: “I’m not sure No 10 has the story right and I fear it will be handled badly, but on welfare – they have got no choice.”

Ministers are trying to make a moral argument – that sorting out welfare is a mission, that it’s better for people’s well-being and health to have a job. Wes Streeting, the health secretary, will almost inevitably make that case when he joins us in the studio tomorrow. That argument was made by Labour in the election and in its manifesto. But the second part of the expected plans – squeezing payments to disabled people who may already be struggling – was not.

None of the hordes of Labour MPs elected for the first time in 2024 had taking cash from the worst off on their campaign leaflets or Facebook posts. But are the newbies, barely a year into the job, the kind of tribe to cause trouble? Of course, it’s important to note they don’t all think the same but talking to some of them, there are some characteristics you can trace.

Remember more than half of Labour’s MPs – 243 out of 406 – are completely new, so understanding their centre of gravity is hugely important. And it seems very different to the previous generations.

PA Media

PA MediaOne of the newbies told me: “Even more than the welfare stuff, the moment that was most revealing about how different we are to 1997 was the 3% defence target and the aid cuts.” This wasn’t met with any more resistance than the resignation of International Development Minister Annaliese Dodds and a “few rumblings” from inside the party – but for most of the 2024 intake it was a “no-brainer”, given the need to spend more on defence as the world becomes less secure.

It’s not just that Labour’s recruits are different, but they note their political upbringing is different too: “We have come of age politically in a time when chaos is the norm and the world feels like it is continually going to hell” – so cutting aid and other policies that are uncomfortable for moderates a generation above “are not that troubling”.

Indeed, some of the newbies have been unkindly branded “toadies” by others, as another source describes them – not just accepting some of the leadership’s tougher plans, but even egging them on, busy writing public letters, or giving supportive interviews.

Whether on welfare, defence or planning, another MP describes them as “pop-up pressure groups”, publicly calling for No 10 to push its reforms harder, and further.

“Aren’t they hilarious?” a party veteran jokes, gently mocking the ambition of those involved, suspicious that the leadership may have gently encouraged a few aspirant MPs to make their case vigorously and loudly.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA government source acknowledges there is a significant chunk of MPs who want to be helpful to the leadership, but with many in marginal seats, “they are not swots, they are street fighters” who are closer to their voters’ concerns. They’re telling the leadership they can give them space to be more radical on welfare, immigration or getting houses built.

For now, whatever the motivation of the usual suspects, No 10 can enjoy a level of unity in the governing party.

It’s also plain that the political operation in government has improved since the summer, in part due to his chief of staff, Morgan McSweeney, credited by many for bringing a new discipline to the party. “There is only one tribe,” a senior figure told me, “it’s Morgan McSweeney’s – it’s his way or the high way – his people are controlling things at the moment.” That’s described differently by others, who say: “It’s Keir’s party now.” And an increasingly confident prime minister abroad has more clout at home.

Shutterstock

ShutterstockBut the rows over welfare that will bubble up this week and the chancellor’s decisions in the Spring Statement next week still certainly matter. Not every MP or activist agrees with the decisions being taken by the centre – but with a whopping majority, the risk is not about losing votes.

It’s about a direction of travel and the perception of the party to the public. It matters in the next few weeks on the inside of government because managing unhappiness takes up political time, energy and effort. It matters outside because rows over policy, whether welfare or immigration, create headlines, and headaches, and the danger of giving the public the impression that the party in charge is not pulling together.

That’s acknowledged by a government source observing the journey Sir Keir’s Labour Party has been on: “We were united against the hard left, then we were united against the Tories” – but as the government settles in, it’s less clear what the party is united on now.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Leave a Reply