Home affairs correspondent, BBC Scotland

PA Media

PA MediaOn the day police found a second body behind a house once occupied by a murderer, the father of a missing teenager raised his hand, crossed his fingers and said he hoped it was his daughter.

Dinah McNicol was 18 when she vanished in 1991, after hitchhiking home to Essex from a dance music festival in Hampshire.

Her father had spoken to countless reporters since then and it just so happened that I was interviewing him when 16 years of tortuous uncertainty were coming to an end.

Ian McNicol had been left in such a dark place that he wanted his daughter to be the person in a shallow grave, because it would mean the family would finally know where she was, get her back, and lay her to rest.

His words laid bare the terrible cruelty of serial killers and they’ve haunted me ever since.

A new BBC documentary, The Hunt for Peter Tobin, explains how the murder of a young Polish student finally solved the mystery of what had happened to Dinah and a second teenager, 15-year-old Vicky Hamilton, who had gone missing in central Scotland six months earlier.

Tobin was a registered sex offender on the run from the authorities when he killed Angelika Kluk and concealed her body beneath the floor of a Glasgow church in September 2006.

He was 60 at the time. The crime was so horrific, detectives were convinced he must have killed before.

Strathclyde Police launched Operation Anagram, a nationwide scoping exercise which tried to establish whether Tobin could be linked to unsolved cases around the UK.

Within months, officers realised he was living in Bathgate when Vicky Hamilton went missing in the West Lothian town in February 1991.

PA Media

PA MediaDespite a huge inquiry and appeals by her distraught family, 15 years had passed with no trace of Vicky ever being found.

The link with Tobin changed everything.

Forensic scientists re-examined evidence from the time of her disappearance and found DNA from Tobin’s son on Vicky’s purse, which had been left near Edinburgh bus station.

In June 2007, Lothian and Borders Police searched Tobin’s former home in Bathgate. In the attic, they discovered a knife which bore traces of Vicky’s DNA.

Operation Anagram went on to connect Tobin to Dinah, who’d gone missing at the other end of the country in August 1991.

Her cash card had been used in towns across the south-east of England, from Hove to Margate and Ramsgate in Kent.

The money draining from Dinah’s account was compensation she received after her mother Judy died in a road accident when she was six.

The police found evidence linking Tobin to the card and established he was living in Margate when Dinah failed to come home.

PA Media

PA MediaOne of Tobin’s neighbours recalled “Scottish Pete” digging a deep hole in his back garden around that time.

Essex Police thought they were going to get answers for Ian McNicol and his family when they went to Tobin’s old house at 50 Irvine Drive in November 2007 – but instead of Dinah, they found Vicky.

Having covered the search in Bathgate, I travelled south to Margate with a sense of disbelief which was shared by the Scottish officers investigating Tobin’s past.

Everyone in Scotland knew the face of the smiling schoolgirl with the bobbed dark hair.

The discovery of her remains so far from home was horrifying and baffling. How had she ended up there?

The answer was that Tobin had killed Vicky in Bathgate, dismembered her body, and taken her remains with him when he moved to a new house 470 miles away in the south of England.

In the days that followed, as the police continued their search for Dinah at Irvine Drive, I interviewed her dad at his home in Tillingham, a small Essex village built round a Norman church.

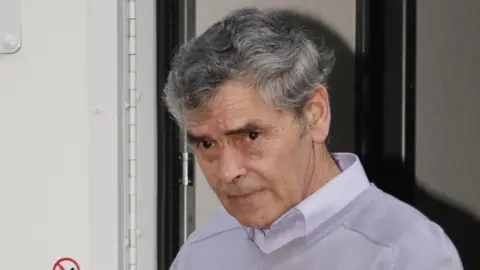

PA Media

PA MediaIan was an instantly likeable man in his late 60s; a retired musician originally from Glasgow who’d named his daughter after a jazz standard.

Over the years, Dinah’s disappearance had taken its toll on his health. We sat down and started filming.

“When I lost my wife, we knew she was dead because we had to bury her,” he said.

“We went through the normal process of grief.

“When a member of your family goes missing, it’s 20 times worse than death because you do not know a thing and all sorts of things go through your imagination.”

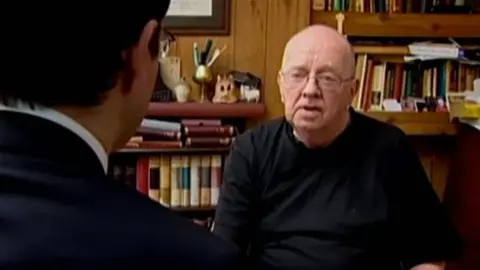

STV/Firecrest Films

STV/Firecrest FilmsHe was taking some solace from the fact that another family in exactly the same situation had been helped, even though his daughter had not been found.

Ian turned to the camera to address Vicky’s family and said: “If you’re watching, from me and my family, good luck to you. We wish you all the best.”

The doorbell rang. Another reporter told us the police had just announced the discovery of a second body.

Ian agreed to continue the interview, raised his right hand with his fingers crossed and said: “If they’ve said that, please be Dinah, and get us out of this misery.

“I would bury her next to her mother. So please, let it be Dinah.”

Later, after the police confirmed the remains were those of his daughter, Ian said he could die in peace. He passed away in 2014.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the BBC documentary, Vicky’s younger sister Lindsay Brown tells of the impact her disappearance had on their mother Jeanette. Two years after Vicky went missing her mother died, her family said, from a broken heart.

Archive footage shows Lindsay reading a statement to the media outside the High Court in Dundee in 2008, on the day Tobin was convicted of Vicky’s murder, flanked by her older sister Sharon and twin brother Lee.

Given all they had been through, what she did that day was as brave as it was difficult to watch.

She said: “Vicky was much more than the girl who was abducted and killed by a stranger or a girl on a missing poster. We will always remember Vicky as she lived, not as she died.”

The detectives investigating Tobin’s past were certain he had other victims. They did all they could to find answers for other families, to no avail.

Tobin took his secrets to the grave and was serving three life sentences when he died in 2022.

No-one came forward to claim his body. His ashes were disposed of at sea.

When I was interviewed for the BBC documentary, the producer asked what I had thought when I heard the news.

I told him I had been pleased and hoped his death hadn’t been pleasant. Should I have been that honest? Did it cross a line? I don’t know.

What I do know is that I’ll never forget Ian McNicol or what he said to me 17 years ago: “Please be Dinah.”

Leave a Reply