BBC News

Handout

HandoutThree judges who oversaw Family Court hearings involving Sara Sharif in the years before she was murdered can be named for the first time following a legal appeal.

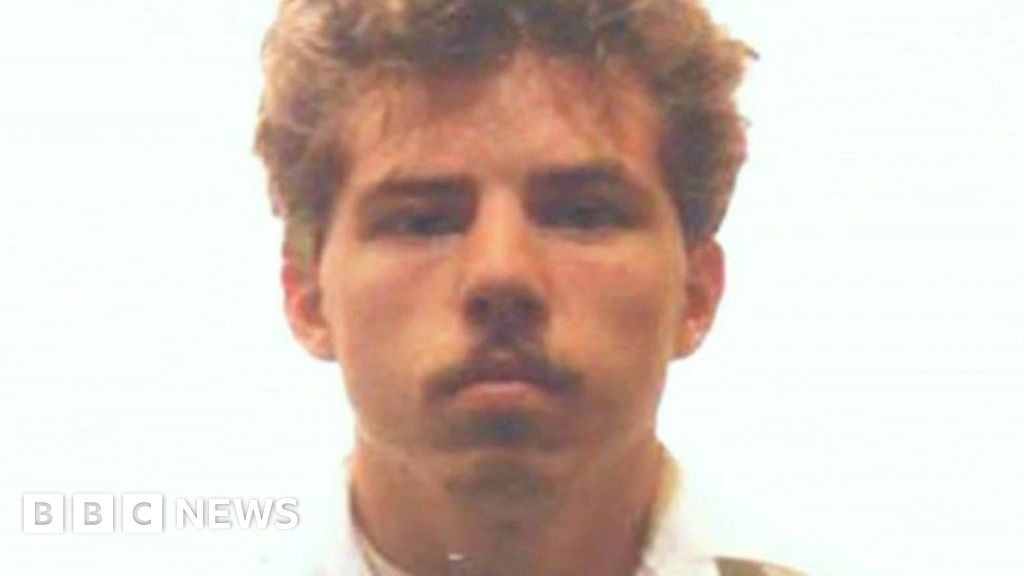

Sara’s father Urfan Sharif, 43, and stepmother Beinash Batool, 30, have been jailed for life for her murder in Woking, Surrey in 2023.

Following their convictions, the media were able to publish details from previous Family Court hearings relating to Sara’s care before her death.

However, a High Court ruling prevented the media from naming the three judges involved in the case, Judge Alison Raeside – who sat on most of the hearings, Judge Peter Nathan and Judge Sally Williams.

Mr Justice Williams, who made the High Court order, said there had been a “real risk” of harm to the judges from a “virtual lynch mob”.

Media organisations, including the BBC, successfully appealed, arguing that judges must expect “their decision-making to be the subject of public scrutiny”.

The most senior civil judge in England and Wales, Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls, found in favour of the media saying “the whole idea of anonymising the judge was, I have to say, misguided”.

Now the judges can be named, we can report that Judge Alison Raeside sat on the earliest hearings involving Sara, the last one, and most of the hearings in between.

The court was involved with the family before Sara was even born, and the first time her name is mentioned was on 17 January 2013. She was six days old.

Surrey County Council was seeking an interim care order – it wanted Sara and two of her siblings to be temporarily taken into foster care until a final decision was made.

The hearing was before Judge Raeside, sitting as a family judge at Guildford County Court.

Police

PoliceShe was told there were concerns that Sara and her siblings were “not adequately supervised”, and that two of them had “unexplained injuries”.

The judge was also told that Urfan Sharif had subjected Sara’s mother Olga Sharif to domestic abuse.

Social workers had asked for the children to be taken into care. They said concerns about the family dated back to May 2010 – almost three years before Sara was born – when one of the siblings had been found alone in a local shop.

Judge Raeside heard that as far back as November 2010, there had been allegations that Urfan Sharif had beaten Olga Sharif and Sara’s older siblings, though she decided not to press charges. Police had then been called to the home on three occasions in 2011 and 2012 after complaints of further domestic abuse.

Judge Raeside decided against a care order and made an interim supervision order instead, saying that Sara and her siblings could stay with their parents under the supervision of Surrey County Council Children’s Services while further assessments were prepared.

The final hearing was delayed to 19 September 2013 and on that day Judge Raeside again decided the children should stay with their parents under supervision. By this time social workers had changed their recommendation to a “supervision order”.

Just over a year later, in November 2014, the case was back before the Family Court after one of Sara’s siblings said Olga had bitten them.

Olga Sharif had been charged with assault and Surrey council made an urgent application for the children to be taken into foster care.

The emergency hearing was heard by Judge Peter Nathan, but the next day the case was before Judge Raeside again.

She decided that Sara and one of her siblings could return to live with Urfan Sharif. The sibling who had been bitten was placed into foster care.

At a hearing the following year, Judge Raeside was told that Surrey council was still extremely concerned at the risk of harm to Sara.

One of her siblings had said that Urfan Sharif had punched them and slapped them with a belt on the bottom.

On the second day of the three-day hearing Olga Sharif announced she was separating from Urfan Sharif because of domestic violence.

She said that in the past Urfan Sharif had poured a flammable liquid on her and tried to set it alight.

On other occasions she said Urfan Sharif had held a knife to her throat and tried to strangle her with a belt. She said home life with Urfan Sharif was like living in a prison. She moved into a women’s refuge and the children moved with her.

In July 2015, another judge, Judge Sally Williams, had Sara and her sibling taken into temporary foster care after reports that Urfan Sharif had been secretly seeing them while they were still at the refuge.

That September, Judge Raeside agreed an interim care order that meant Sara and her sibling stayed for a while in foster care. But in November, she ordered that the children could live with their mother Olga Sharif, with Urfan Sharif getting supervised access.

For the next few years the family courts were not involved with the family, and on 1 February 2019 Judge Raeside was promoted. She was appointed as the designated family judge for Surrey. But a few months after that the family were back in front of her again.

By now Urfan Sharif had a new wife Beinash Batool. He was asking the court to sanction arrangements for Sara and her sibling to live with them with Olga Sharif getting some supervised contact. The court was told Olga Sharif had already agreed to this.

Judge Raeside heard that Sara and her sibling had complained that Olga had mistreated them, and they had already started living with their father and stepmother. Sara had apparently said her mother had slapped her and pulled her hair, and had tried to burn her with a lighter and drown her in the bath. It had been Urfan Sharif who first raised the allegations.

A social worker who was asked to prepare a report for the court also recommended that Sara and her sibling should live with their father and step-mother with supervised contact with Olga Sharif.

On 9 July 2019, Judge Raeside, who by now had been involved in hearings involving the family for more than six and a half years, agreed that Sara and her sibling should live with their father Urfan Sharif and stepmother Beinash Batool – the two people who would kill her five years later – “it is ordered that the children do live with the father and Ms Batool”, she said.

They were both convicted in December 2024 of murdering Sara Sharif.

The judge who ordered the anonymity of the judges said that if anything it was the system rather than individuals that should be held up to public scrutiny.

In a judgment Mr Justice Williams said: “In this case the evidence suggests that social workers, guardians, lawyers and judiciary acted within the parameters that law and social work practice set for them.

“Certainly to my reasonably well-trained eye there is nothing (save the benefit of hindsight) which indicates that the decisions reached in 2013, 2015 or 2019 were unusual or unexpected.”

“Based on what was known at the time and applying the law at the time I don’t see the judge or anyone else having any real alternative option.”

The lawyer acting for newspapers and broadcasters including the BBC, Adam Wolanski KC said judges were “the face of justice itself” and must expect “their decision-making to be the subject of public scrutiny.”

On Friday, the highest ranking judge in England and Wales announced the formation of a “security taskforce” to assess how to better protect the safety of judges.

In a letter seen by the PA news agency, Chief Justice Baroness Carr said that incidents were “becoming all too common”, and she was “increasingly concerned” about threats made to judges on social media.

The naming of the judges comes just days after new rules came in permitting reporting from family courts in England and Wales.

Leave a Reply