Getty Images

Getty ImagesChancellor Rachel Reeves said on Wednesday that “economic growth is the number one mission of this government” as she unveiled a series of proposals to boost the UK’s economy.

But how quickly could the government get growth from the plans she announced?

Critics have argued some of the projects – such as expanding Heathrow – would not help in the near term.

BBC Verify has examined some of the key numbers and claims.

How slow is the UK’s growth?

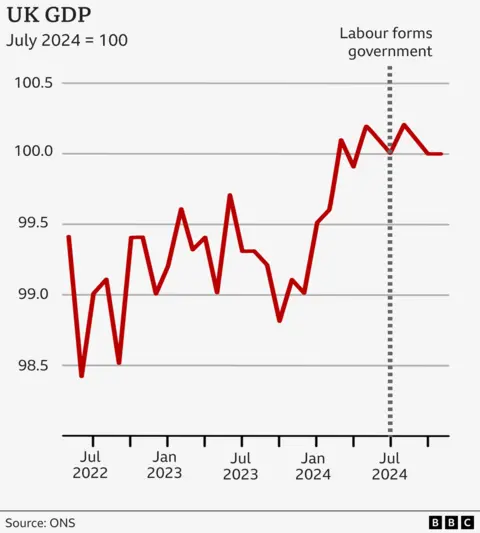

The most recent official data shows there was virtually no growth in GDP – the overall size of the UK economy – between the July 2024 election and November 2024.

And the latest medium term official growth forecast from the Office for Budget Responsiblity, the government’s official forecaster, is for 1.6% GDP growth in 2029, which would be well below the pre-2008 financial crisis average growth of 2.8% a year.

However, the International Monetary Fund has forecast that the UK’s growth rate for 2025 and 2026 will be higher than in France and Germany.

Lower rates of GDP growth would translate into slower growth in our wages and incomes and general living standards.

Heathrow expansion

The chancellor said that allowing Heathrow to build a third runway would “create 100,000 jobs”, boost investment and exports and “unlock futher growth”.

She cited a new report by the consultancy Frontier Economics which found it could increase the UK’s potential GDP by 2050 by 0.43%, around £17bn.

That is broadly in line with the findings of an independent commission by Sir Howard Davies in 2015, which concluded a third runway at Heathrow would support UK trade and enhance productivity and push up GDP by 0.65-0.75% by 2050 relative to otherwise.

However, most analysts believe it would likely take many years before shovels went into the ground to start building a new runway, even with new reforms to speed up the planning process.

And the government will have a difficult balancing act to both expand Heathrow and meet its climate goals.

BBC Verify asked the Treasury for its source for the 100,000 jobs figure and it pointed to a 2017 report by the Department for Transport estimating that a new runway at Heathrow could add between 57,000 and 114,000 additional local jobs. Though that report added that “these jobs are not additional at the national level, as some jobs may have been displaced from other airports or other sectors.”

Oxford-Cambridge Growth Corridor

The chancellor in her speech claimed an Oxford and Cambridge Growth Corridor “could add up to £78bn to the UK economy by 2035”.

This corridor is a resurrection of the previous government’s plans to join Oxford and Cambridge with new transport links and allow those two university and research hubs to expand.

In support of the chancellor’s figure, the Treasury has cited research by an industry group called the Oxford-Cambridge Supercluster.

This research shows that this £78bn is a “cumulative figure” over 10 years, not the boost in a given year.

The analysis suggests the project could add £25bn in Gross Value Added (GVA) a year to the UK economy by 2035.

That would constitute roughly a permanent 1% boost to UK GDP by that date.

EPA

EPAEstimates of the impacts of an infrastructure project on growth are inherently uncertain and very sensitive to the assumptions of researchers about what would have happened to growth if it had never been built.

Yet most economists do believe infrastructure projects, especially those that allow already productive places to expand, will ultimately help the UK economy grow more rapidly than otherwise.

Ben Caswell, a senior economist at The National Institute of Economic and Social Research (Niesr), said: “Big infrastructure projects typically deliver growth over the long term, approximately 10 to 20 years.”

“There may be a small demand side boost in the short term when shovels are in the ground, but nothing so significant that you would see it in headline GDP growth figures.

“However, after the project is complete, the supply capacity of the economy is permanently enhanced, and, all other things equal, that delivers higher sustained GDP growth than would have otherwise been.”

Pensions reform

Another reform the chancellor says will be pro-growth is enabling UK companies to access the funds from their “defined benefit pension” pots, held on behalf of their workforces to fund their retirement.

Defined benefit pension schemes guarantee an annual pension payment to retired workers, based on their salary while they were in work.

Many of these defined benefit pension pots have moved into surplus in recent years due to the rise in interest rates since the pandemic, meaning their financial assets (their investments) are greater than their financial liabilities (what they have to pay out to pensioners).

The Treasury has said that approximately 75% of schemes are now in surplus and that the total surplus adds up to £160bn.

The chancellor wants to legislate to allow the firms to use these funds to invest, while keeping safeguards to protect and guarantee workers’ pension pay-outs.

Measuring the size of the surplus of defined benefit scheme depends on various complex assumptions about the scheme and its relationship to the employer.

The official Pension Regulator estimates that on one measurement the size in September 2024 was £207bn, but £137bn on a different measurement.

The Treasury’s estimate is roughly midway between the two.

If such sums were deployed that could, in theory, make a positive difference to overall UK business investment, which is regarded by economists as both a short term and a long term driver of GDP growth.

Total business investment in 2023, according to official data, was £258bn.

But the size of any boost from this pension reform would depend on companies being willing to invest their surpluses, which is subject to great uncertainty as many firms have been looking to offload their defined benefit pension schemes to insurance companies in recent years.

Leave a Reply