Idlib, Syria

BBC

BBCAyghad never thought that his dream of returning to his farmland could turn into a nightmare.

He fights his tears as he shows us a picture of his late father, smiling and surrounded by abundant olive trees in their land in Idlib province, northwestern Syria.

The picture was taken five years ago, a few months before forces linked to the former government took over their village, near the city of Saraqeb.

The city was a strategic stronghold for Syrian opposition factions for years, before forces allied with the fallen regime of Bashar al-Assad launched an offensive against rebels in Idlib province at the end of 2019.

Hundreds of thousands of residents fled their homes, as Assad forces took over several other rebel strongholds in the northwest by early 2020.

Ayghad and his father were among those displaced.

“We had to leave because of the fighting and air strikes,” Ayghad says, as the tears fill his eyes. “My father was refusing to leave. He wanted to die in his land.”

The father and son longed to return ever since. And when opposition forces regained control of their village in November 2024, their dream was about to come true. But disaster soon struck.

“We went to our land to harvest some olives,” Ayghad explains. “We went in two separate cars. My father took a different route back to our home in the city of Idlib. I warned him against it, but he insisted. His car hit a landmine and exploded.”

Ayghad’s father died instantly at the scene. Not only did he lose his dad that day, but he also lost his family’s main source of income. Their farmland, spread across 100,000 square metres, was filled with 50-year-old olive trees. It’s now been designated a dangerous minefield.

At least 144 people, including 27 children, have been killed by landmines and unexploded remnants of war since Bashar al-Assad’s regime fell in early December, according to the Halo Trust, an international organisation specialising in clearing landmines and other explosive devices.

The Syria Civil Defence – known as the White Helmets – told the BBC that many of those killed were farmers and landowners who were trying to go back to their land after the Assad regime collapsed.

Unexploded remnants of war pose a grave threat to life in Syria. They’re mainly split into two categories. The first are unexploded ordnances (UXOs) like cluster bombs, mortars and grenades.

Hassan Talfah, who heads the White Helmets team clearing UXOs in north-western Syria, explains that these devices are less challenging to clear because they are usually visible above ground.

The White Helmets say that, between 27 November and 3 January, they cleared some 822 UXOs in north-western Syria.

The bigger challenge, Mr Talfah says, lies in the second category of munition – landmines. He explains that former government forces planted hundreds of thousands of them across various areas in Syria – mainly on farmland.

Most of the deaths recorded since the Assad regime fell happened on former battle front lines, according to the White Helmets. Most of those killed were men.

Mr Talfah took us to two huge fields riddled with landmines. Our car followed his on a long, narrow and winding dirt road. It’s the only safe route to reach the fields.

Along the sides of the road, children run around the area. Hassan tells us they are from families who have recently returned. But the dangers of mines surround them.

As we get out of the car, he points to a barrier in the distance.

“This was the last point separating areas under the control of government forces from those held by opposition groups” in Idlib province, he tells us.

He adds that Assad forces planted thousands of mines in the fields beyond the barrier, to stop rebel forces from advancing.

The fields around where we stand were once vital farmlands. Today, they are all barren, with no greenery visible except for the green tops of land mines that we can see using binoculars.

With no expertise in clearing land mines, all the White Helmets can do for now is cordon these fields off, and hammer down signs along their borders warning people off.

They also spray-paint warning messages on dirt barriers and houses around the edges of the fields. “Danger – landmines ahead,” they read.

They lead campaigns to raise awareness among locals about the dangers of entering contaminated lands.

On our way back, we come across one farmer in his 30s who has recently returned. He tells us that some of the land belongs to his family.

“We couldn’t recognise any of it,” Mohammed says. “We used to plant wheat, barley, cumin and cotton. Now we cannot do anything. And as long as we cannot cultivate these lands, we will always be in poor economic condition,” he adds, clearly frustrated.

The White Helmets say they have identified and cordoned off around 117 minefields in just over a month.

They are not the only ones working to clear mines and UXOs, but it seems that there is little co-ordination between the efforts of various organisations.

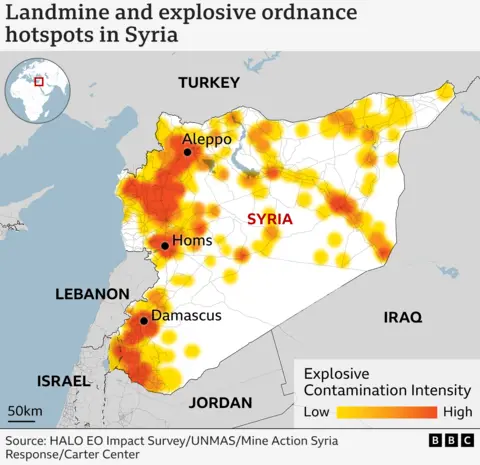

There are no accurate statistics for the areas contaminated with UXOs or landmines. But international organisations, such as the Halo Trust, have drawn up approximate maps.

Halo Syria programme manager Damian O’Brien says that a comprehensive survey needs to be done for the country to understand the scale of contamination. He estimates that around a million devices would need to be destroyed to protect civilian lives in Syria.

“Any Syrian army position is quite likely to have some landmines laid around it as a defensive technique,” Mr O’Brien says.

“In places like Homs and Hama, there are entire neighbourhoods which have been almost completely destroyed. Anybody going into those structures to assess them, for either demolition or to rebuild them, needs to be aware that there may well be unexploded items in there, whether it’s bullets, cluster munitions, grenades, shells.”

BBC News

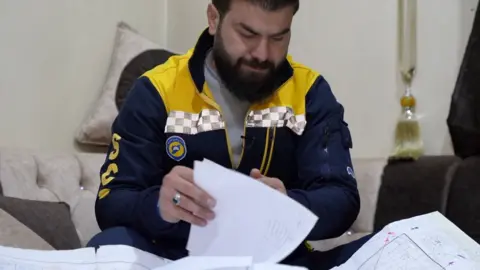

BBC NewsThe White Helmets came across a treasure trove that could aid efforts in clearing mines. In their office in the city of Idlib, Mr Talfah shows us a stack of maps and documents, left behind by government forces.

They show locations, numbers and types of mines planted in different fields across northwestern Syria.

“We will hand over these documents to the bodies that will deal with landmines directly,” Mr Talfah says.

But the local expertise currently available in Syria does not seem to be enough to combat the serious dangers that unexploded munitions pose to civilian life.

Mr O’Brien stresses that the international community needs to work alongside the new government in Syria to improve expertise in the country.

“What we need from donors is the funding, to be able to expand our capacity, which means employing more people, buying more machines and operating over a wider area,” he says.

As for Mr Talfah, clearing UXOs and raising awareness about their dangers has become a personal mission. Ten years ago, he lost his own leg while clearing a cluster bomb.

He says that his injury, and all the heart-breaking incidents he’s witnessed of children and civilians impacted by UXOs, have only fuelled his persistence to keep working.

“I never want any civilian or team member to go through what I have,” he says.

“I cannot describe the feeling I get when I clear a danger threatening the life of civilians.”

But until international and local efforts are coordinated to neutralise the danger of landmines, the lives of many civilians, especially children, remain at risk.

Leave a Reply