Michael Jackson’s death is a reminder of the vitality of America’s (and the world’s) cult of celebrity. The intensity of the global public response moves one to ask: why is society so deeply affected by the death of a person who was known for bizarre behavior and questionable judgment? Evolutionary psychology provides a helpful perspective.

When evolutionary psychologists observe that a behavior is widespread and common in a particular species, they first seek to find out whether such behavior is “adaptive,” meaning, beneficial from a reproductive point of view. Hero-worship is interesting in this respect because we find versions of it in all societies. Our earliest recorded literature, the Epic of Gilgamesh, was concerned primarily with the lives of two heroes. From Odysseus to Elvis, great performers have evoked veneration. Why?

Public performance can be understood as a form of genetic signaling. This is one reason why young animals play. When puppies frolic and run about playfully, they are sending very serious messages to future competitors and future mates about their genetic fitness. A puppy that is especially big or fast in play is communicating with competitors (“you won’t want to mess with me when I grow up”) and future mates (“my genes are the best – you’ll have great kids with me”).

It makes sense, therefore, for youngsters to enjoy play (they do) and to be great “show-offs” (they are). In fact, the whole purpose of play, from an evolutionary perspective, is precisely to “show off” our exceptional genetic fitness. As we grow older and mature into sexually active adults, we don’t really stop playing. Instead, our play becomes deadly serious (we begin to call it “work” or “art”), and many of us become even more extreme “show-offs”. We’d better. Our “performances” on the job or in social occasions are the most likely indicators of whether or not we will succeed in the reproductive marketplace.

Although there are many ways of displaying genetic fitness, humans appear especially attuned to verbal, musical or athletic performance. Our top politicians, actors, musicians and sports stars receive overwhelming adulation. Verbal and musical displays likely evolved as a form of competitive play meant to signal intelligence. “Playing the dozens” and hip-hop dissing contests probably have roots in human behavior stretching back hundreds of thousands of years. As humans evolved into more intelligent creatures, the pressure of sexual selection put a premium on displays correlated with intelligence.

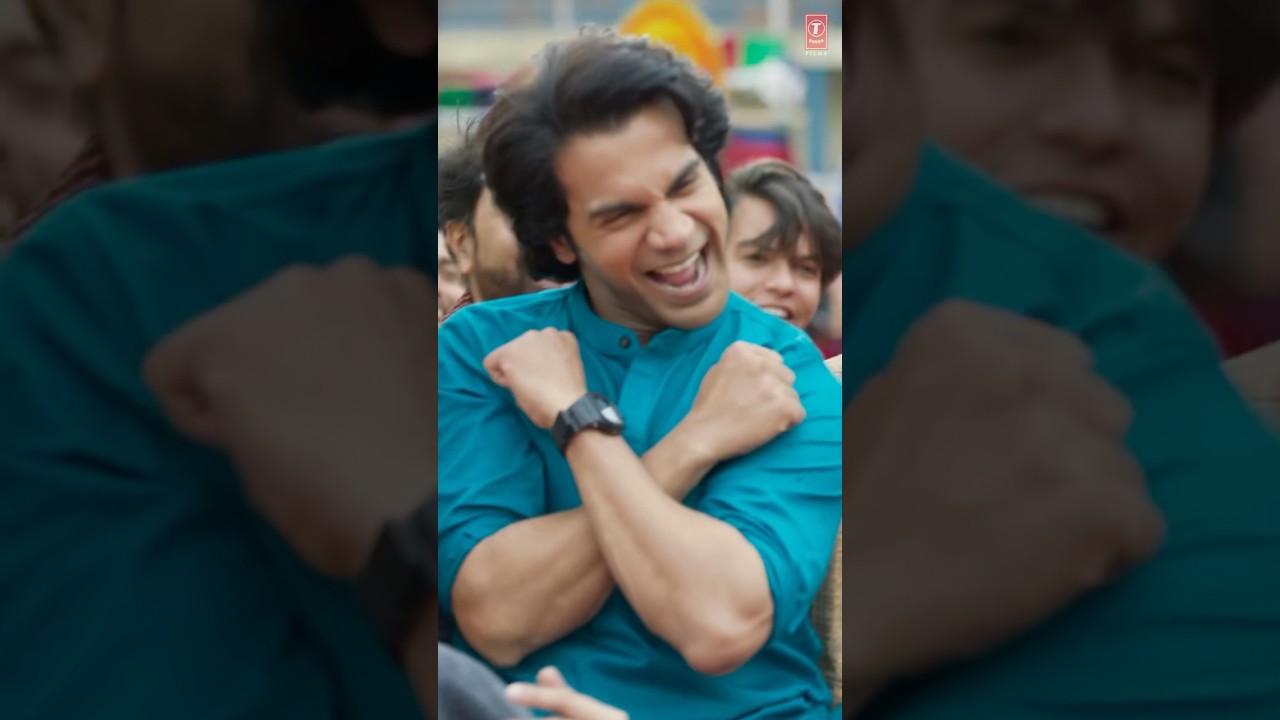

Thus, when musical superstars perform in public, they are inserting an ancient evolutionary key into a special lock in our brains. When the key turns, we receive an exhilarating blast of dopamine, the brain’s own version of cocaine, the ultimate feel-good drug.

The fascinating thing about public performance is that it feels good to the performer as well as to the audience. Again, from an evolutionary perspective, this is to be expected. The performer’s brain is being rewarded because evolution has provided a great stimulus (a dopamine fix) for us to show off successfully whenever we can get away with it. Doing so maximizes our chances of attracting a desirable mate. Showing off feels good. Showing off in front of a large audience feels great.

The audience also finds its brains rewarded by evolution as well, but for different reasons. Why do we enjoy watching exceptional performances? There are three reasons. First, spectacular performances are in a sense “instructive”. Humans are the most imitative species on earth. Much of our intelligence has to do with our ability to model and mimic adaptive behavior. It makes sense for us to be especially attentive to superior performance of any kind – the more we enjoy it, the closer we will pay attention to it, and the more likely that we will learn something from it. Second, if we feel that we are somehow socially or emotionally linked to the performer, we are encouraged by the increased chance that we or our offspring will share in the genetic bounty represented by that performer. Third, the more we ingratiate ourselves with the performer, as by displaying submissive and adoring behavior, the more likely we are to earn the performer’s esteem, and with it, a chance to mate with the performer and endow our offspring with the performer’s superior genes.

It seems likely that humans have been programmed by evolution to turn either into rock-stars or groupies (or both). Which path we take depends on our location within the competitive space of our generation’s gene-pool. If we are the best singer or dancer of our generation, we will be tempted to perform: the rewards, both in terms of our brain’s dopamine revels and in the attention of sexually-attractive mates, could be huge.

Unfortunately, while it makes sense – from an evolutionary perspective — for members of our species to be attracted to musical genius, it does not necessarily make sense from an individual perspective. Many people have learned this in the most concrete way, by marrying musicians (I did). My eldest son inherited exceptional musical talent, so my genes are happy. My genes were never concerned with my wife’s operatic temper (she’s a mezzo-soprano), that’s been purely my affair. Evolution promises us adorable children; it doesn’t promise us a rose garden.

Michael Jackson’s fans have to some extent been tricked by evolution. Watching the Gloved One’s uncanny gyrations and masterful crooning released entire oceans of their cerebral dopamine, but that did not change the fact that their hero was a very weird man.

Indeed, Michael Jackson’s life represents the very opposite of wisdom, the opposite of what one should admire or seek to emulate in a role-model. Dopamine-rushes can be addictive, exactly like cocaine. Young Michael’s success as a child prodigy may have destroyed his chances for happiness as an adult. He was never able to improve upon the Peter Pan-like ecstasies he achieved as a child star, so he spent his life in a perpetual attempt to remain a child. This is already very unhealthy at age 20 or age 30. At 40 or 50, it is a sign of mental illness.

Evolution has left our brains vulnerable to deceptive evolutionary keys. Fortunately, it has also endowed us with an alarm system called “reason.” We can learn to recognize our ancient evolutionary triggers for precisely what they are – stimuli to do things that may or may not be good for us. Nothing can stop that dopamine from flowing once our fingers start snapping to “I’m Bad,” but our reason can stop us from taking the whole thing too seriously. And it should.

We should not disparage the pleasures and delights of participation in spectacles. Whether we find ourselves cheering in a sports stadium or at a jazz concert, our delight is deep and real. We should indulge in this joy – it is one of the highlights of human experience. However, we should look for role models in the people we really know and trust around us, not in musical superstars, no matter how gifted.

Leave a Reply